Julia Morgan: The Visionary Architect Who Redefined California’s Skyline And Women’s Place in Design

From Hearst Castle to seismic-resistant campuses and cultural landmarks, her fingerprints remain etched across California

Julia Morgan never cared for fame—she was too busy rewriting the architectural rulebook while everyone else was still debating whether women should even own drafting tables. In an era when the profession was a closed club with a strict “no women allowed” sign, she quietly marched in, took a seat, and then redesigned the room with better light, stronger foundations, and superior seismic integrity. Her legacy is a masterclass in understatement: no scandals, no bravado, no quotable outbursts—just hundreds of impeccably crafted structures standing taller than any headline she ever refused to give.

The Trailblazer Who Didn’t Ask for Permission

Julia Morgan’s journey began in San Francisco in 1872, a time when architecture was widely seen as a gentleman’s pursuit. Undeterred, she enrolled in civil engineering at UC Berkeley, a field only marginally more welcoming. There, she caught the attention of Bernard Maybeck—an early mentor who recognized her gift for structure and detail. With his encouragement, Morgan set her sights on the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the world’s most prestigious architecture school.

Getting in was hard. Getting in as a woman was nearly impossible. Morgan attempted the entrance exam multiple times—each attempt part grit, part genius, and part crusade. When she finally earned admission in 1898, she became the school’s first female architecture student. It was a symbolic crack in a very reinforced glass ceiling.

The First Woman To Shape California

Upon returning to the United States, Morgan wasted no time. In 1904, she became the first woman licensed as an architect in California. But instead of celebrating, she simply got to work—quietly, obsessively, and with the kind of precision most clients didn’t know they needed until she delivered it.

Her early projects showcased her fearlessness with reinforced concrete, a material that was cutting-edge at the time. When the devastating 1906 earthquake struck San Francisco, Morgan’s structures—like the Mills College bell tower, El Campanil—stood firm. It was one of the first seismic engineering success stories in the state’s history, and Morgan’s reputation rose with the same steady confidence as her buildings.

Hearst Castle: A Collaboration Written in Stone (and Marble, and Tile…)

Of all her clients, none was more demanding—or more creatively driven—than William Randolph Hearst. Their partnership spanned nearly three decades and culminated in her most famous creation: Hearst Castle at San Simeon.

Part Mediterranean palace, part fever dream, part logistical puzzle, the estate showcased Morgan’s ability to translate ambition into reality without losing her sanity or her design integrity. She coordinated vast teams of artisans, managed budgets, adapted to Hearst’s constantly changing ideas, and executed one of the most complex private constructions in American history. Yet she approached it with her signature low-key discipline, proving that immense projects don’t require immense egos—just immense talent.

Champion Of Spaces For Women And Community

While Hearst Castle hogs the spotlight, Morgan’s work for women’s organizations may be her most meaningful legacy. She was the architect of choice for the YWCA, designing dozens of buildings across the country—swimming pavilions, recreational centers, residences, community halls—spaces that promoted empowerment, education, and dignity at a time when such environments were rare.

Her structures were warm without being whimsical, welcoming without being indulgent, and always grounded in safety and accessibility. Morgan didn’t just build for women; she built with an understanding of their needs long before inclusivity became architectural practice.

A Style Defined By Adaptability, Not Ego

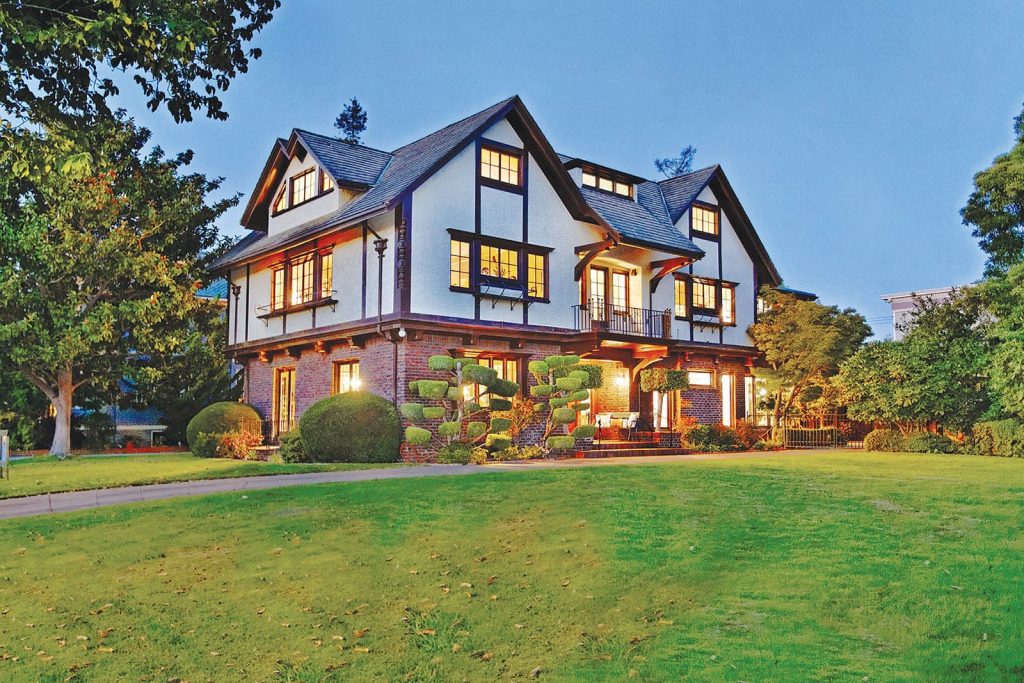

What makes Morgan so difficult to categorize—yet so endlessly fascinating—is her refusal to be pinned to a single architectural style. Mission Revival, Tudor, Mediterranean, Arts and Crafts—she worked across genres with the ease of someone fluent in multiple visual languages.

To her, architecture wasn’t a trademark. It was a service. Her buildings were never about flaunting her identity; they were about elevating the lives of the people inside them. In a profession obsessed with signature flourishes and artistic ego, Morgan’s humility was a radical act.

The Legacy Of A Reluctant Icon

By the time she retired in 1951, Julia Morgan had designed over 700 structures—private homes, civic buildings, university landmarks, and grand estates that turned into tourist attractions. But she avoided the limelight with the same precision she applied to her blueprints. No interviews. No public lectures. No victory laps.

Her posthumous recognition has been slow but richly deserved. In 2014, she became the first woman awarded the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal—a long-overdue tribute to a career spent quietly reshaping the American West.

Today, Julia Morgan remains a study in contrasts: a private person who created public spaces, a pioneer who didn’t preach, an innovator who rarely explained herself. Her greatest statement was her work—and her buildings are still speaking, still standing, and still remindi