Who Was Antoni Gaudí? The Visionary Architect Who Rewrote the Language of Design

A deep dive into the life and legacy of Antoni Gaudí, the Catalan master whose organic forms, bold structures, and spiritual imagination reshaped modern architecture, exploring how he became one of the most celebrated architects of the 20th century and the timeless creations that define his genius

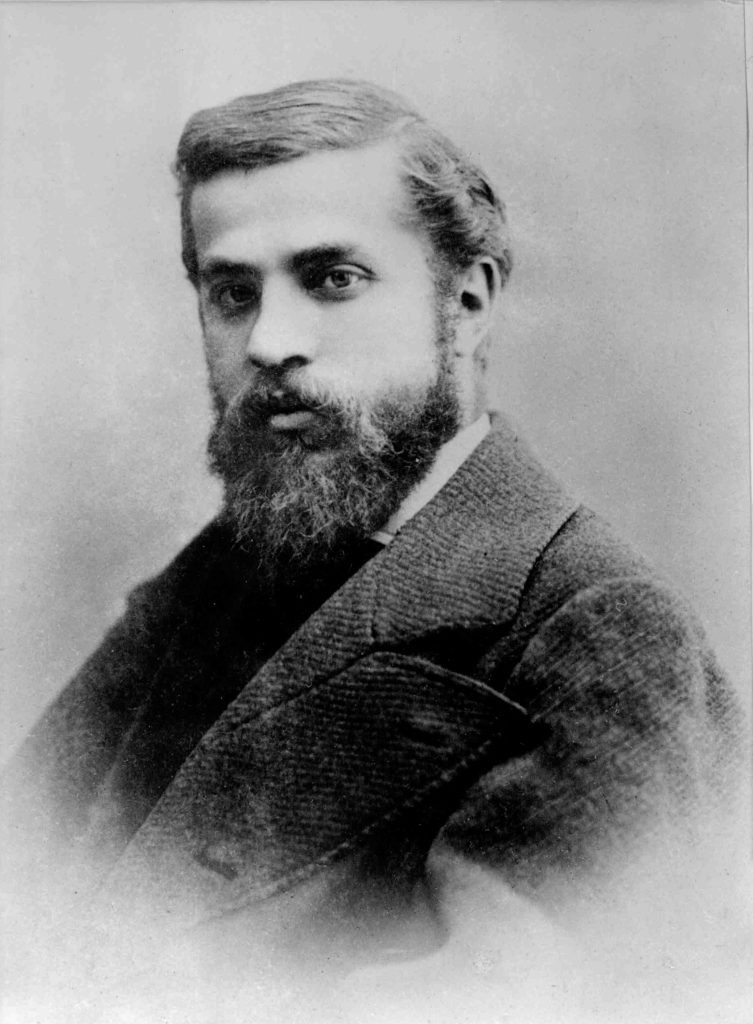

Antoni Gaudí was not merely an architect. He was a visual storyteller, a sculptor of dreams, and a man who believed that nature held the blueprint for every great form. Born in 1852 in Reus, Catalonia, Gaudí grew up surrounded by the Mediterranean landscape’s curves, colours, and textures—an environment that later became the living foundation of his architectural language. At a time when European architecture leaned toward order and uniformity, Gaudí rejected the straight line, embracing instead the swirl of a seashell, the slope of a hillside, the organic harmony of trees and flowers. This conviction shaped some of the most recognisable works in modern architecture, structures that seem part earthly, part otherworldly.

Early Influences And The Making Of A Modernist Icon

Gaudí’s training at the Barcelona Higher School of Architecture exposed him to Gothic revival, Moorish motifs, and the emerging modernisme movement. Yet even as a student, he began bending tradition to his will. His drawings displayed an instinctive command of geometry and a fascination with light, leading professors to remark that genius and madness often walk hand in hand. Upon graduation, he joined the wave of architects transforming Barcelona during the late 19th century—yet from the start, Gaudí set himself apart, infusing projects with personal symbolism and an artisanal richness that challenged the rigidity of conventional design.

A Philosophy Rooted In Nature And Spirituality

What made Gaudí truly revolutionary was his belief that architecture should be as alive as the world around it. He studied animal skeletons, plant growth, and the geometries of crystals, translating these principles into archways, facades, and interiors. His use of catenary arches, hyperbolic paraboloids, and helicoidal columns reflected not just technical skill but a profound understanding of natural engineering. At the same time, Gaudí’s spirituality deepened with age. His later works, especially the Sagrada Família, carry the unmistakable imprint of religious devotion, merging divine inspiration with engineering innovation.

Sagrada Família The Eternal Masterpiece

No discussion of Gaudí is complete without the Sagrada Família, the towering basilica that has become emblematic of Barcelona itself. Commissioned in 1883, it quickly grew into a lifelong undertaking, consuming his final decades with monastic dedication. The basilica’s soaring facades, each narrating a biblical chapter, reveal a poetic fusion of Gothic tradition and radical structural experimentation. Inside, the columns rise like trees, branching toward a canopy of stained glass that bathes the space in shifting colours. Although Gaudí completed only a fraction of the basilica before his untimely death in 1926, his detailed models enabled future architects to continue the project. Nearly a century later, the Sagrada Família still ascends, a living memorial to his visionary genius.

Casa Batlló

Among Gaudí’s most celebrated residential works, Casa Batlló stands as an oceanic dreamscape. Its flowing façade of mosaic tiles, mask-like balconies, and skeletal contours earned it the nickname “House of Bones.” Inside, light wells swirl with aquatic hues, and curved lines guide every movement, removing the slightest trace of angularity. A short distance away lies Casa Milà, or La Pedrera, whose rough-hewn stone exterior recalls a windswept cliff. The rooftop, populated with surreal sculptural chimneys, feels like a battleground of mythical guardians. Both buildings broke away from the rigid grid of Barcelona’s city planning, offering instead a breath of movement, fantasy, and structural innovation.

Park Güell

Commissioned as part of an ambitious residential development, Park Güell became an architectural garden of imagination. From its serpentine bench to its gingerbread-like gatehouses, the park blends urban design with fairy-tale whimsy. Gaudí masterfully integrated the site’s natural slope and vegetation, crafting viaducts and pathways that appear to grow organically from the earth. Today, it remains one of Barcelona’s most visited sites—a testament to Gaudí’s ability to blur the boundaries between architecture, landscape, and sculpture.

A Legacy That Lives Beyond Time

Antoni Gaudí’s death, the result of a tram accident in 1926, shocked Barcelona. Yet his legacy was far from finished. Decades later, his works were recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and architects worldwide continue to study his daring use of geometry, structure, and symbolism. Gaudí demonstrated that architecture need not conform to rigid rules; it can breathe, ripple, and evoke emotion. His buildings stand as permanent reminders that creativity flourishes where imagination refuses to be contained.