The Art of Spin: How Tourbillon Balances Gravity And Time

Once a marvel of 18th-century ingenuity, the tourbillon has evolved into a symbol of horological mastery

There’s something almost rebellious about the tourbillon — a mechanism that literally spins in defiance of gravity. It’s the horological equivalent of a ballerina performing pirouettes inside a hurricane: poised, beautiful, and impossibly precise. What began as Abraham-Louis Breguet’s 19th-century solution to a very practical problem has since evolved into a mechanical spectacle — a tiny, spinning universe that no watch connoisseur can resist staring at. It’s part physics, part poetry, and entirely overengineered, which might just be why the world still can’t stop talking about it. In an age of quartz perfection and digital dominance, the tourbillon stands as a defiant celebration of motion, imperfection, and the pursuit of mastery — and yes, the question that keeps watch lovers up at night: Can this thing ever actually stop?

A Revolution In The Pocket

The story starts with one man and one frustrating flaw. Back in 1801, Abraham-Louis Breguet — the godfather of modern horology — faced a conundrum. Pocket watches of the era kept wildly inconsistent time because gravity affected their escapements when kept in a single upright position. His solution? Put the escapement and balance wheel into a tiny rotating cage that made a full revolution every 60 seconds, effectively “averaging out” the pull of gravity.

It was genius. A literal whirlwind — the tourbillon — that danced through every gravitational position, ensuring timepieces became dramatically more accurate. At the time, this wasn’t a vanity feature; it was a technological breakthrough. The tourbillon wasn’t designed to impress; it was designed to correct.

From Science To Symbolism

Fast-forward two centuries, and the tourbillon is no longer fighting gravity — it’s defying convention. When wristwatches replaced pocket watches, the gravitational advantage mostly disappeared, but the allure of the spinning cage only grew stronger. Today, it’s no longer about necessity; it’s about prestige.

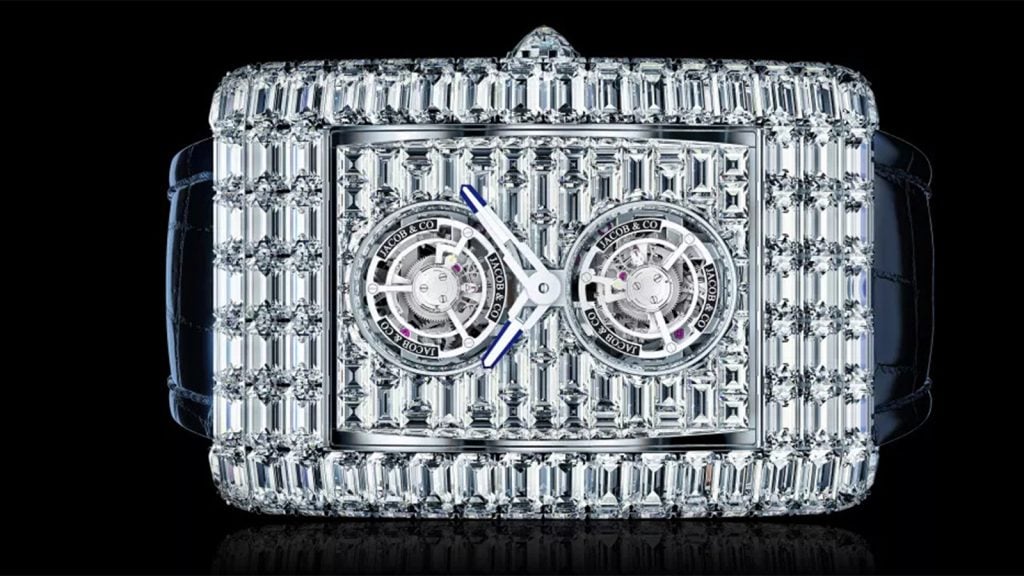

In the world of haute horlogerie, a tourbillon is the equivalent of a car’s V12 engine or a bespoke Savile Row suit — unnecessary, extravagant, and utterly magnificent. It’s how brands flex their craftsmanship. Audemars Piguet crafts double and triple-axis tourbillons that pirouette in multiple directions. Greubel Forsey turns the mechanism into sculptural art, while Bulgari’s Octo Finissimo Tourbillon compresses the entire marvel into a case barely thicker than a coin.

The irony? The complication originally built for performance has now become the ultimate aesthetic indulgence — the mechanical signature of those who understand that too much precision can still be beautiful.

How the Tourbillon Works — The Dance of Mechanics

The principle behind the tourbillon is deceptively simple but fiendishly hard to execute. The balance wheel and escapement — the regulating organs of a watch — sit inside a rotating cage that turns once per minute. This constant motion averages out errors caused by gravity when the watch remains in a fixed position.

But achieving that rotation is no small feat. The entire cage often weighs less than a gram and consists of dozens of parts — bridges, pivots, jewels — all meticulously hand-finished. The tolerance for error? Virtually zero. Even the tiniest imbalance could throw off the rotation and defeat its purpose. It’s a delicate equilibrium, a ballet of brass and steel where motion itself becomes precision.

It’s why the tourbillon’s beauty is inseparable from its complexity — every second it spins, it’s a visible reminder of human obsession with time, symmetry, and perfection.

Can A Tourbillon Be Stopped?

Now for the question every watch nerd eventually asks: can a tourbillon be stopped? After all, it seems in perpetual motion — spinning defiantly, like it’s powered by pride itself. Technically, yes. When you pull the crown of a watch to set the time, a mechanism called the hacking lever stops the balance wheel. But in a tourbillon, the balance and escapement are part of the rotating cage — meaning you’d have to halt the entire cage to stop time. Most traditional tourbillons don’t support this because it risks damaging the delicate assembly.

However, innovation has never been far from horology. A. Lange & Söhne’s 1815 Tourbillon cracked the code with a patented stop-seconds mechanism — the cage halts instantly when the crown is pulled, allowing precise synchronization down to the second. Moritz Grossmann’s BENU Tourbillon offers a similarly clever solution, gently braking the cage with a sophisticated lever system. Still, most tourbillon owners prefer to let it spin freely — because, really, stopping a tourbillon feels a bit like telling a comet to pause mid-flight.