Beaux-Arts Architecture Explained: History, Key Features And Famous Buildings

Beaux Arts architecture was born in the studios of Paris shaped by academic perfection and went on to transform cities into stages of grandeur where classical discipline met theatrical ambition

Beaux Arts architecture did not believe in subtlety. It believed in arriving making an entrance and staying firmly in your memory long after you had left the building. This was architecture trained in Paris educated in classical perfection and unleashed on the modern city with absolute confidence. Columns were bigger staircases were grander and facades were composed as if every building expected an audience. In an age of industrial progress and rising national pride Beaux Arts buildings stood like well dressed aristocrats among factories and tenements reminding everyone that culture refinement and spectacle still mattered. If architecture were a performance Beaux Arts would demand a standing ovation.

This style rooted in classical Greek and Roman traditions refined through academic training at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. It emphasises symmetry hierarchy and formal composition combined with rich decorative detail. Unlike earlier classical revivals Beaux Arts focused on grand planning dramatic spatial sequences and visual impact making buildings feel ceremonial and monumental. The style flourished from the late nineteenth to early twentieth century particularly in civic institutional and cultural architecture.

Also Read: Italianate Architecture Explained: History, Defining Features, Iconic Buildings And Architects

Key Features Of Beaux Arts Architecture

Beaux Arts buildings are defined by strict symmetry monumental scale and carefully organised facades. Common features include grand staircases central domes colonnades sculptural reliefs and lavish interior detailing. Plans are highly structured with axial layouts that guide movement through a sequence of ceremonial spaces. Materials such as stone marble and bronze are used generously reinforcing the sense of permanence and authority. Every element serves both aesthetic and symbolic purpose.

Beaux Arts And The Rise Of Monumental Cities

As cities expanded rapidly during the industrial age Beaux Arts architecture provided a visual language of order and grandeur. The style became closely associated with civic pride and national identity. Major boulevards railway stations museums libraries and government buildings adopted Beaux Arts principles to convey stability and progress. Urban planning movements such as the City Beautiful movement in the United States drew heavily from Beaux Arts ideals shaping entire city centres around monumental axes and public spaces.

Architects Who Defined Beaux Arts Architecture

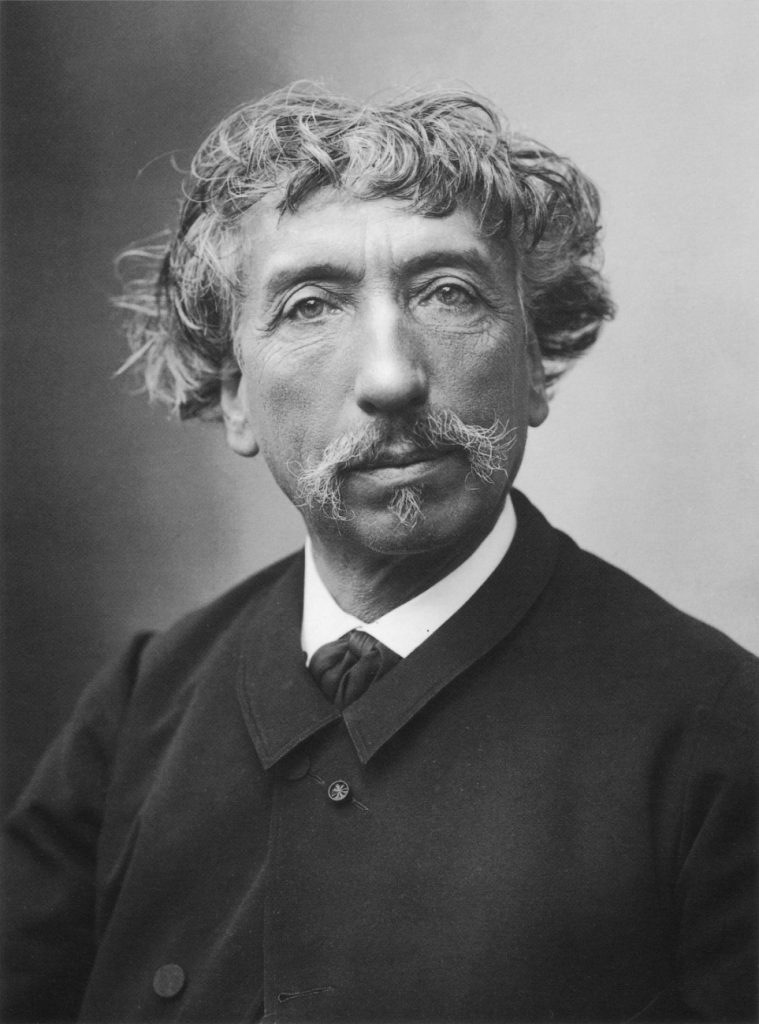

Prominent architects associated with Beaux Arts include Charles Garnier whose Paris Opera House remains the style’s most iconic masterpiece. In the United States architects such as Richard Morris Hunt, Daniel Burnham, McKim Mead and White championed the style through major public and private commissions. Their work established Beaux Arts as the architectural language of prestige education and power across continents.

The Enduring Legacy Of Beaux Arts Design

Although modernism later rejected its ornament and formality Beaux Arts architecture never truly disappeared. Its principles of symmetry planning and civic presence continue to influence contemporary institutional design. Many Beaux Arts buildings remain among the most beloved landmarks in their cities valued for their craftsmanship grandeur and cultural symbolism. Restoration efforts worldwide highlight the enduring respect for this architectural tradition.

Famous Beaux Arts Buildings Around The World

Palais Garnier, Paris, France

The Palais Garnier stands as the ultimate expression of Beaux Arts architecture and the building against which all others are measured. Designed by Charles Garnier and completed in the late nineteenth century this Paris Opera House is a celebration of symmetry ornament and theatricality. Its grand staircase gilded interiors sculptural facades and layered spatial drama turn architecture into performance. Every surface communicates luxury power and cultural confidence making it the most iconic Beaux Arts building in the world.

Also Read: What Is Mediterranean-Style Architecture? Features, History, And Design Explained

Grand Central Terminal, New York City, United States

Grand Central Terminal proves that infrastructure can be monumental art. Completed in 1913 this transportation hub embodies Beaux Arts planning principles through its axial layout soaring concourse and celestial ceiling. The facade balances classical restraint with civic scale while the interior sequence elevates daily movement into ceremony. It remains one of the most successful examples of Beaux Arts architecture serving both functional and symbolic roles in a modern city.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States

The grand facade of The Metropolitan Museum of Art exemplifies Beaux Arts monumentalism adapted for cultural education. Designed by Richard Morris Hunt and later expanded the museum presents a disciplined classical frontage that communicates permanence and authority. Its monumental steps columns and sculptural detailing establish the museum as a civic temple to art reinforcing the Beaux Arts belief that culture deserved architectural grandeur.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, Mumbai, India

Formerly known as Victoria Terminus this landmark blends Beaux Arts planning with Indo Gothic ornamentation creating one of the most distinctive civic buildings in the world. Designed during the British colonial period the structure combines grand symmetry axial planning and monumental scale with local craftsmanship and decorative richness. It demonstrates how Beaux Arts principles were adapted globally to express power modernity and cultural identity in diverse contexts.