Inside The World’s Most Beautiful Libraries: Where Books Meet Architecture

These are not rooms that merely store books, but architectural sermons on knowledge, ambition, and the quiet power of ink on paper

There was a time when knowledge was not downloaded, but approached with reverence, when one entered a library as one might a cathedral, hat metaphorically in hand and ego suitably diminished. These were not places for haste or distraction, but carefully composed theatres of thought, where architecture conspired with silence to remind the visitor that ignorance was a personal failing and learning a noble pursuit. Columns rose like moral arguments, ceilings soared with theological certainty, and shelves stretched endlessly as if daring the reader to give up. In these libraries, books do not simply exist; they preside. What follows are five such sanctuaries, where architecture and intellect meet not politely, but magnificently.

Admont Abbey Library, Austria

The Admont Abbey Library is less a room for reading and more a baroque hallucination brought under strict intellectual control. Completed in 1776, it is the largest monastic library hall in the world, and possibly the most theatrical. White and gold dominate the space, punctuated by ceiling frescoes that depict the stages of human knowledge with unapologetic allegory. Light pours in through tall windows, bouncing off gilded ornamentation and marble floors, making the pursuit of wisdom feel like a well-lit moral obligation. Every curve, column, and statue reinforces the idea that faith and reason were once believed to be elegant companions rather than argumentative rivals.

Also Read: Train Stations With Incredible Architecture Designs Around The World

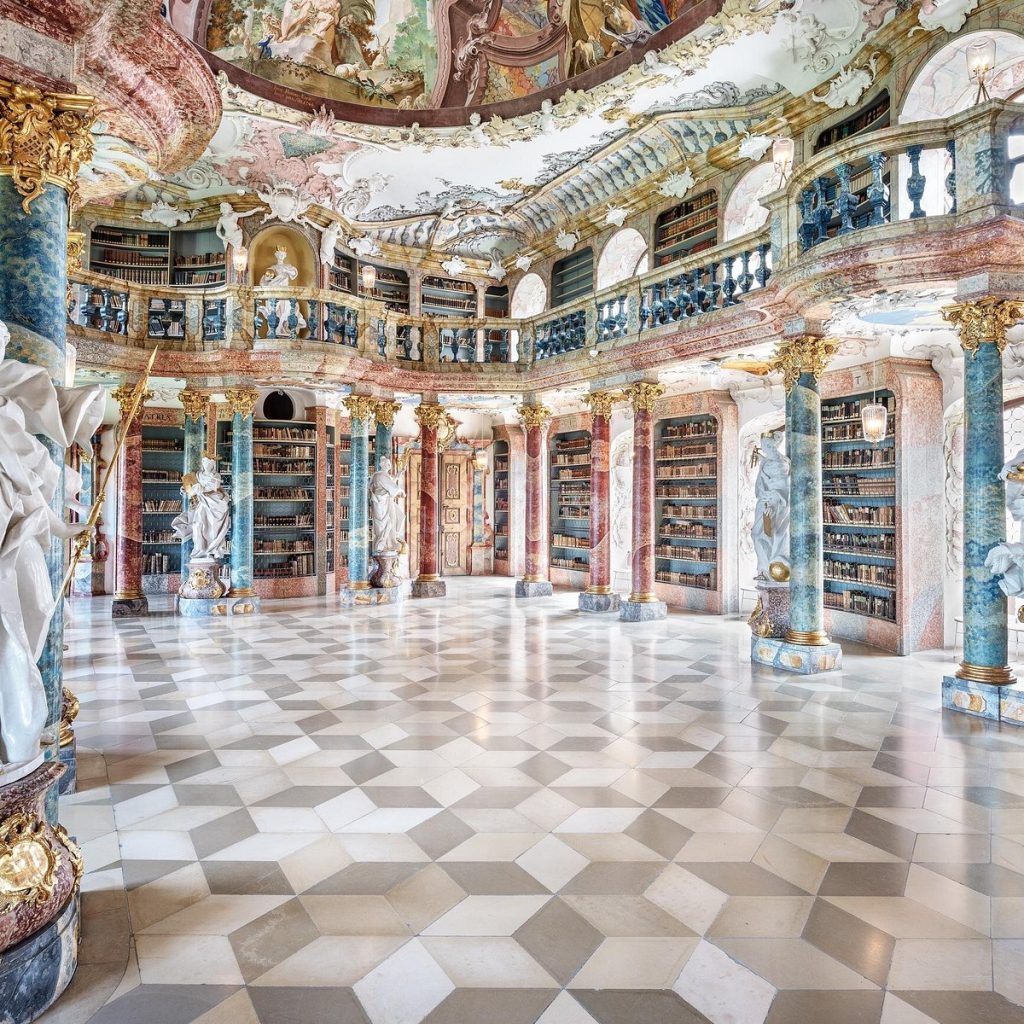

Wiblingen Abbey Library, Germany

Wiblingen Abbey Library is baroque intellect softened by celestial optimism. Completed in the mid 18th century, it is instantly recognisable by its pastel palette, sculptural columns, and ceiling fresco that seems to dissolve the boundary between architecture and heaven. Unlike darker monastic libraries designed to intimidate, Wiblingen feels almost weightless, its symmetry and gentle colours suggesting that knowledge is not a burden but a form of liberation. The books are housed in restrained shelving, deliberately allowing the room itself to deliver the sermon. It is scholarship presented not as penance, but as grace.

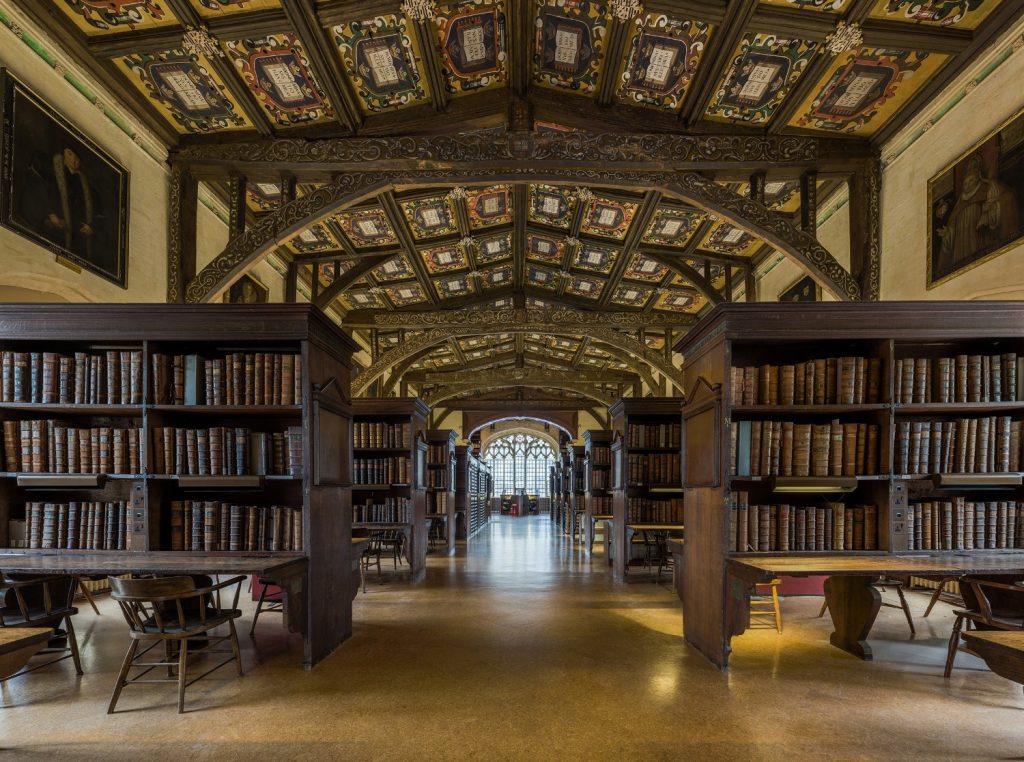

Duke Humfrey’s Library, England

Hidden within Oxford’s Bodleian Library, Duke Humfrey’s Library is the embodiment of English academic stubbornness and dignity. Dating back to the late 15th century, it is long, narrow, and resolutely unimpressed by modernity. Dark wooden shelves line the walls, chained books whisper of an era when theft of knowledge was a genuine concern, and the timbered ceiling hangs low with scholarly gravitas. This is not a space designed to comfort the casual reader; it is a room that expects commitment. One does not browse here casually. One studies, or one leaves, suitably chastened.

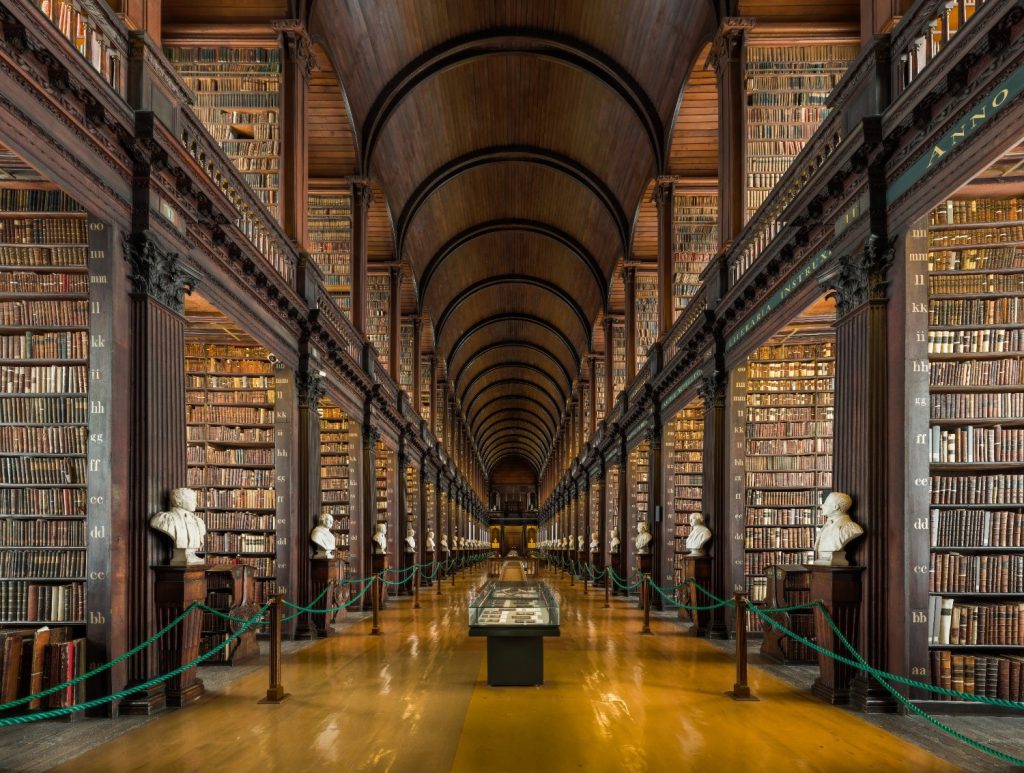

The Library of Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

The Long Room at Trinity College Dublin is perhaps the most instantly recognisable library interior in the world, and with good reason. Stretching nearly 65 metres, its barrel vaulted ceiling and endless ranks of dark oak shelves create a perspective so commanding it borders on the cinematic. Marble busts of philosophers and writers stand in stoic judgement along the aisle, silently reminding visitors of the intellectual lineage they are trespassing upon. Housing over 200,000 of the library’s oldest books, the Long Room feels less like a storage space and more like a physical manifestation of collective memory, beautifully heavy with consequence.

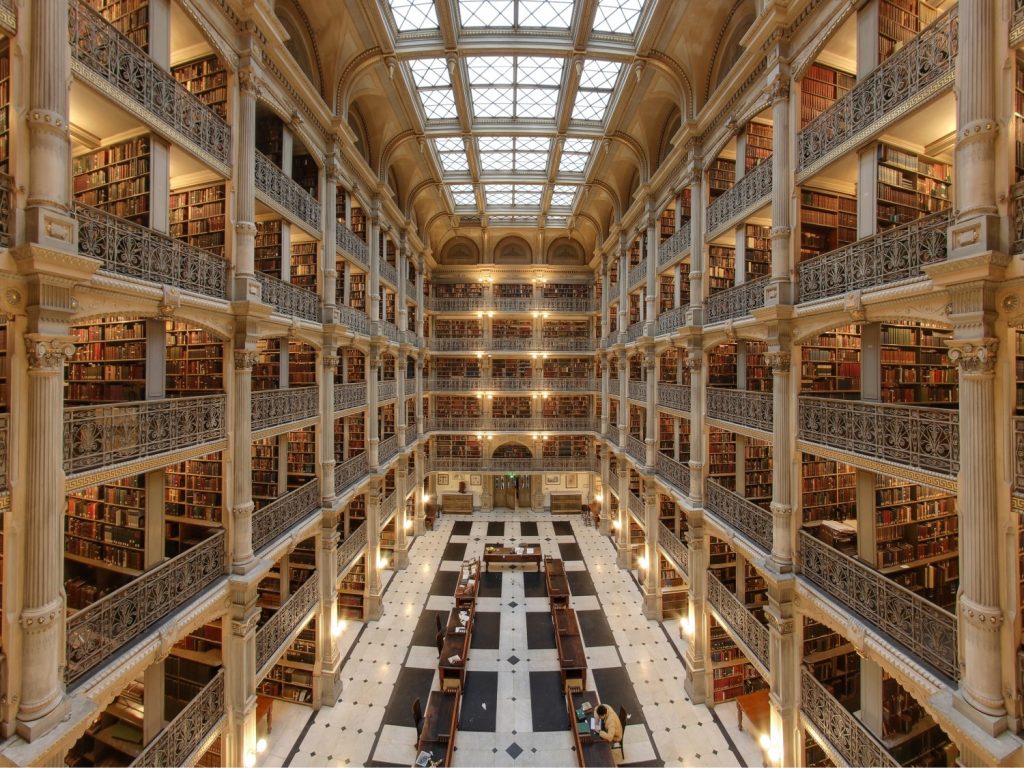

George Peabody Library, USA

The George Peabody Library in Baltimore is American optimism rendered in iron, marble, and sky high ambition. Opened in 1878, its soaring central atrium rises six tiers high, lined with ornate cast iron balconies that frame the space with almost operatic drama. Natural light floods in from a vast skylight, illuminating rows of leather bound volumes arranged with almost military precision. Unlike its European counterparts, this library carries a certain democratic confidence. Knowledge here is not cloistered or whispered about; it is displayed boldly, proudly, and with the unmistakable belief that learning should inspire awe rather than intimidation.