‘Design Is A Form Of Self-Enquiry’: Pinakin Patel On His 50 Year Retrospective ‘The Turning Point’ At Nilaya Anthology Mumbai

Ahead of his first retrospective tracing five decades of Pinakin Patel, the multihyphenate gets candid about Indian Essentialism, the complexities of being too aware, and his Alibaug shift for an organic lifestyle

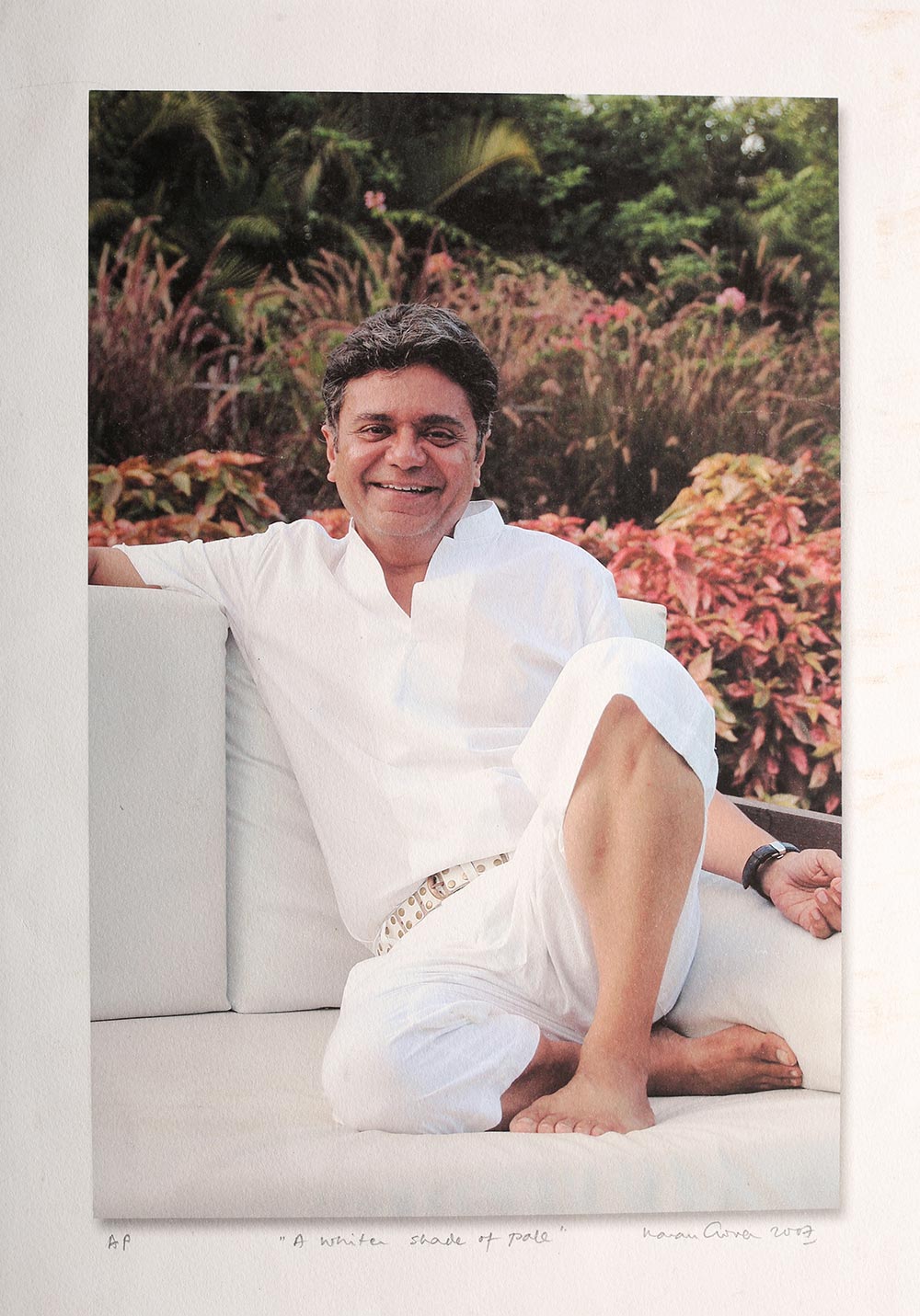

Self-taught architect, and designer and Pinakin Patel was naturally drawn to “things of beauty” as a child. “Very early on, I realised that my life’s journey would be guided by a search for beauty. That led me to discover beauty in the design of buildings, interiors, furniture, fashion, even cinema,” opens the 72-year-old designer extraordinaire over our Zoom interview, whose creative practice is as wide as his life spread across Mumbai, and later in Alibaug in pursuit of an organic lifestyle.

As someone who never formally studied design and took it instinctively, for Patel, design is a form of “self-enquiry”. It’s a tool to probe every design choice: which materials to use, which to filter out, how design can be in tune with ethics and environment and its use in problem solving. And it’s with this conscious design ethos rooted in Indian Essentialism that Patel built his sustainable home in Alibaug back in 1999, opened his design store 45 years ago called as the ‘Hamptons of Mumbai,’ set up the Kolkata Centre of Creativity and dedicated a museum to his mentor Dashrath Patel in Alibaug, along with creating a huge body of work.

Putting a spotlight on his 50-year design legacy, Nilaya Anthology Mumbai comes up with ‘The Turning Point’, a rare retrospective of Pinakin Patel’s practice. The multimedia exhibition spanning three months starting January 18, will have an expansive view of Pinakin’s creative life that also shaped India’s contemporary design language. On view will be 11 seminal works, nineteen curated objects from Pinakin’s personal collection, and a film showcase. The exhibit will also have a Dashrath Patel archive, to honour the Padma Shri artist who was one of the first teachers at the National School of Design, Ahmedabad and deeply influenced and mentored Pinakin.

Ahead of the show, we speak to Pinakin about the display, what makes him root for Indian Essentialism and his Alibaug shift in pursuit of slow luxury.

Q: You’ve mentioned in your past interviews that unconventional ideas were not easily accepted back in the day. Did it impact the way you think?

A: I didn’t experience that as regret or longing; it was more an observation in hindsight. As a child or young person, you don’t always recognise these things. Looking back, I realise I was fortunate. I was born into a well-travelled, well-exposed family. We travelled extensively within India and abroad, which gave me a broad cultural lens. That exposure shaped my understanding of quality, beauty, luxury and lifestyle without it being forced or deliberate. And then when it came to applying ideas to work, the resistance was not from any one quarter or segment of people. It came from the absence of a market. There were no reference points before late 80s. People didn’t know how to categorise the luxury lifestyle as it was just coming up. The first real reference points for taste and lifestyle emerged through five-star hotels, which introduced new ways of living — multiple restaurants, cafes and coffee shops, and high-rise buildings. Since foreign travel was limited to a privileged few, hotels became a window to the world. Around the late ’80s and early ’90s, creativity began surfacing across disciplines. Modern art was just beginning to raise its head with the opening of 2-3 prominent art galleries in Delhi and Mumbai, such as Dhoomimal in Delhi and Chemould and Pundole in Mumbai. Kavita Bhartiya was planning to launch Ogaan in Delhi, so she was getting the first band of fashion designers together.

I opened my first store, Etcetera, in Mumbai in 1985, without knowing exactly what it would become, allowing myself the freedom to experiment with fashion and art. With globalisation, India began taking baby steps towards a luxury lifestyle.

Also Read: Bhavna Kakar On Bringing rare Pre-Partition Phulkaris In Delhi

Q: Who were your early influences at a time when there were no reference points in the design field in the 80s?

A: Interior design wasn’t even discussed in India then; architecture was the dominant discipline. Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier left a strong impression on me with his Modernist architecture in Chandigarh. Over time, I also drew inspiration from the minimalist and sharp work of architect and urban planner Charles Correa and B.V. Doshi. In interiors, my exposure came through socially prominent women who travelled abroad and sought refined living experiences, such as philanthropist Parmeshwar Godrej, socialite Zarine Khan, and Mumbai’s Sunita Pitamber, known as a very successful exporter of arts and artefacts. Internationally, I was deeply influenced by tropical Modernists like Geoffrey Bawa and his work in Sri Lanka. I wanted to understand Western design thinking without imitating it, which kept my focus firmly rooted in India and the Eastern aesthetics.

Q: Congratulations on your first retrospective, The Turning Point. Did you have any defining turning points in your life?

A: (laughs) Well…that I have to ask Pavitra (Rajaram). She and her curatorial team came up with the title. I believe it reflects the many transitions in my life, moving across disciplines from interior design to architecture and fashion. And even geographically, when I relocated from Mumbai to Alibaug in 1999 in search of nature, peace and calm in life.

Q: The exhibition will also have Dashrath Patel’s archive. Given he’s your mentor, what can visitors expect?

A: Dashrath Patel represents a pre-existing foundation of Indian design. He was the founder and director of education at NID and India’s first multidisciplinary artist with works spanning art, ceramics, photography, education and whatnot! Destiny brought us together very late in life during his retrospective celebrating 50 years at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) in 1999. Today, it feels poetic that my retrospective celebrating my 5-decade journey includes his archive. Viewers will get to see a historical 80-year trajectory of design evolution from pre-independence to contemporary India through his archive. Alongside the archive, there is a section drawn from my personal art collection, which I’ve been building since I was 18. Art has always flanked my work in homes, public spaces, museums, and galleries. For the duration of the exhibition, 5 decades’ worth of collected works will be displayed.

Q: You’re known for championing “Indian Essentialism.” Can you decode it for us, and some objects you designed on the basis of this?

A: Traditionally, design was explained through minimalism and maximalism or austerity versus excess. But India doesn’t operate in absolutes. In our culture, minimalism and maximalism coexist and shift fluidly. For instance, in our country, a temple deity may be unadorned at dawn and lavishly decorated by morning, having been bathed with milk, honey, water and flowers. Or that one may lead a very simple life all these years and throw an extravagant or maximalist wedding to remember the occasion. So Indian essentialism recognises this in-between grey space where what is essential changes based on time, need, and context. It’s not about choosing extremes but understanding what truly matters at a given moment. One of my earliest things that I designed based on the basis of ‘Indian Essentialism’ was a gadda, realising that I just need one piece of furniture in the home which is essential and multi-functional. It was used for sitting, sleeping, studying, and socialising. Another piece was the Jhula Bed, inspired by India’s cultural relationship with rocking and swings. It was designed as a romantic, functional, celebratory object, something Radha and Krishna might choose for their home (laughs).

Q: How have people’s design preferences changed over the last decade?

A: The biggest shift has been access to information. With digital media, clients today are as informed as designers. They arrive having researched materials, finishes, and trends extensively. That’s why I now call myself a facilitator rather than a designer. This has made collaboration more complex because one doesn’t know who the lead player is, unlike the previous decade, when this awareness did not exist, and roles were well-defined. It’s creating confusion in design and implementation, and we’re witnessing more people being unhappy with each other. I am lucky not to have faced this as I retired 10 years ago (smiles).

Q: Sustainable lifestyle is the new luxury of today. Tell us about your Alibaug shift, what prompted it and how your stay exemplifies sustainability.

I wanted to live a sustainable life long before sustainable living became a rising trend. In Mumbai, my hundred workers had to travel two hours every day, jostling in the local train to reach the workplace, leading tough lives. I had this utopian dream that what if we all lived in a campus in Alibaug and everyone had to just walk to work. It will reduce time, energy, money and even carbon footprint as we won’t be using any transportation or fuel and would be growing our own food, also to lead a healthy life. Real luxury is time, space, personal peace of mind, ease of living, rather than a 100-inch television. That’s an extra. When I moved to Alibaug, I was in search of nature and all these parameters. But back then, nobody was curious about Alibaug despite it being near Mumbai. In fact, the area was ridiculed with jokes like ‘Kya Tum Alibaug Se Aae’ used for ones who were out of sync. But I shifted there, which was seen as a mad decision by people, but today everyone is vocal about this kind of sustainable living.

I built my home with local labour. The design is in tune with the surroundings and climate, where we use Mangalorean sloping clay tiles, which soak water and do not lead to leakage, given Alibaug receives heavy rainfall, lying in the Konkan region. Walls are made with brick and lime plaster, while doors and windows are crafted with old Burmese teakwood. The landscape design by my wife was done in such a way as not to disturb ecology and bird life. Our food was homegrown and freshly cooked just 10 minutes before having it.

Sometimes, I begin to wonder about the drastic changes happening in life and where human life is headed. For instance, Alibaug is being rapidly urbanised and absorbed into Mumbai. It’s disturbing to see that happen without proper urban planning in the name of green expansion. However, this area could have just been left untouched as the green lungs of Mumbai for people to come here for emotional well-being and see another way of living. Design is losing its relevance in retrospect to climate and surroundings. For instance, when I hear glass towers like Dubai may come to Alibaug, I wonder how much air conditioning will be needed and the impact surroundings. But change is inevitable. With such rapid changes, the future of design belongs to the individual.