What Is Vernacular Architecture? Origins, Key Features And Famous Buildings Explained

Rooted in place, shaped by climate and perfected by generations, vernacular architecture proves that the smartest buildings were often built without blueprints or star architect

Before architecture became obsessed with glossy renders, celebrity egos and buildings that look like crumpled paper thrown at the sky, people simply built what worked. No manifestos, no competitions, no pretentious explanations — just shelter designed by common sense and survival instincts. Vernacular architecture is what happens when humans listen carefully to their climate, their materials and their daily routines instead of trying to impress Instagram. Mud walls thick enough to beat desert heat, sloped roofs that laugh at monsoons, courtyards that turn brutal sun into gentle shade — all engineered long before air conditioning or sustainability consultants existed. It’s architecture without arrogance, and frankly, it still outperforms half the buildings going up today.

Understanding Vernacular Architecture As A Living Tradition

Vernacular architecture refers to buildings created using local materials, traditional construction techniques and knowledge passed down through generations. It is not defined by a single style but by its relationship to place. These structures evolve naturally over time, responding to climate, geography, culture and social customs. Rather than being designed by professional architects, they are shaped by communities, resulting in buildings that are practical, efficient and deeply human. Vernacular architecture is not frozen in the past; it adapts, absorbs change and continues to influence contemporary design worldwide.

Climate, Materials And The Intelligence of Place

At the heart of vernacular architecture lies an intuitive understanding of environment. In hot, arid regions, thick earthen walls and small openings regulate temperature naturally. In wet climates, elevated structures and steep roofs manage rainfall with ease. Materials are sourced locally — stone, mud, timber, bamboo — reducing environmental impact long before sustainability became fashionable. This architecture is inherently climate-responsive, proving that comfort can be achieved through design intelligence rather than mechanical intervention.

Prominent Thinkers and Architects Inspired By Vernacular Design

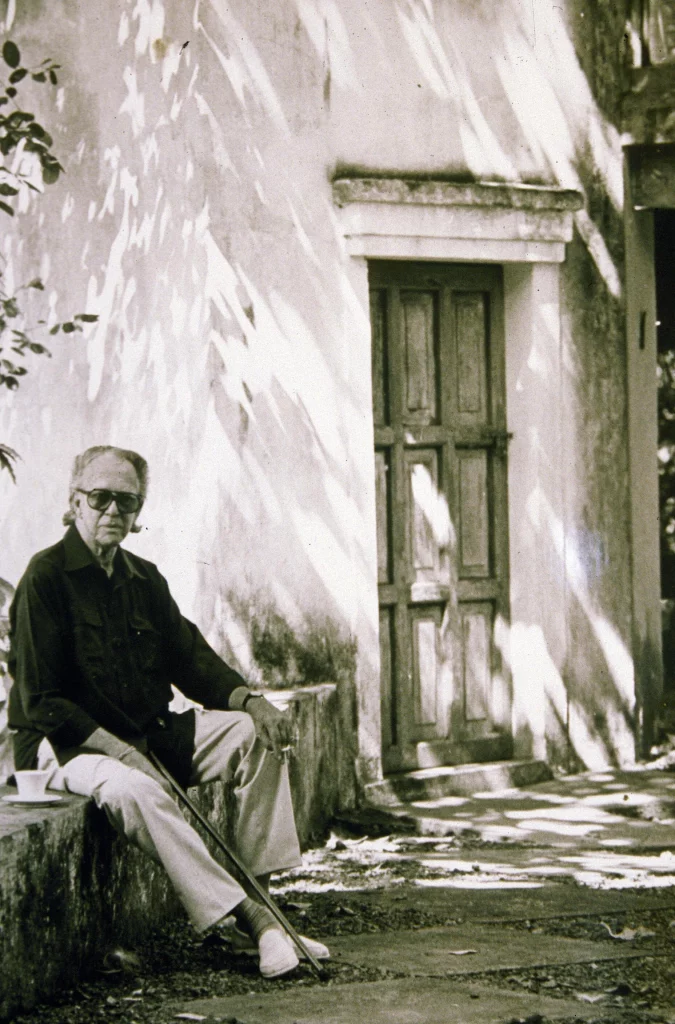

While vernacular architecture itself is anonymous, many influential architects have championed its principles. Hassan Fathy advocated for earth architecture and community-driven building in Egypt, demonstrating how traditional methods could address housing crises. Bernard Rudofsky brought global attention to vernacular wisdom through his landmark exhibition Architecture Without Architects. Geoffrey Bawa fused Sri Lankan vernacular traditions with modernism to create tropical modernism. Laurie Baker popularised cost-effective, climate-sensitive architecture in India using local materials. Even modern masters like Tadao Ando and Peter Zumthor draw heavily from vernacular ideas of light, material honesty and spatial restraint.

Famous Vernacular Buildings Around The World

Across the globe, vernacular architecture manifests in unforgettable forms. The mud-brick houses of Yemen’s Shibam rise like ancient skyscrapers engineered entirely from earth. Rajasthan’s stepwells combine ritual, climate control and monumental beauty. The trulli houses of Alberobello in Italy use dry stone construction perfected over centuries. Japan’s minka farmhouses demonstrate timber craftsmanship and modular living rooted in seasonal change. Kerala’s nalukettu homes revolve around courtyards that manage humidity and social life simultaneously. These buildings are not monuments; they are living systems refined by time.

Vernacular Architecture And Sustainability

Long before green certifications existed, vernacular architecture embodied sustainability by default. Minimal waste, renewable materials, passive cooling and low energy consumption were built into the system. Buildings were repaired rather than replaced and adapted rather than demolished. Today, as architects grapple with climate change and resource scarcity, vernacular principles are being re-examined as essential solutions rather than romantic relics. They offer a blueprint for sustainable living grounded in reality rather than theory.

Modern architecture increasingly borrows from vernacular logic, even when expressed through concrete, steel or glass. Courtyards, shaded transitions, thick walls, perforated screens and regional material palettes all trace their lineage back to vernacular traditions. Contemporary architects reinterpret these ideas to suit modern lifestyles while preserving their environmental intelligence. In doing so, vernacular architecture continues to evolve — not as nostalgia, but as relevance. Vernacular architecture reminds us that buildings do not need to shout to be meaningful. They need to belong. In a globalised world of cloned skylines and interchangeable cities, vernacular design offers identity, resilience and cultural continuity. It teaches architects to observe before designing and communities to value knowledge already embedded in their landscapes. Ultimately, vernacular architecture is not about the past — it is about remembering that the smartest design often comes from listening rather than inventing.