In the evolving discourse on sustainable design, few projects articulate the ethos of environmental stewardship with the poetic clarity of the Lotus Clubhouse in Vietnam. Rather than announcing its presence with architectural bravado, the clubhouse adopts a posture of quiet deference, allowing the surrounding forest and shimmering lake to remain the true protagonists. The structure does not intrude upon the landscape; it converses with it, demonstrating that the most sophisticated architecture is often that which knows when to step back.

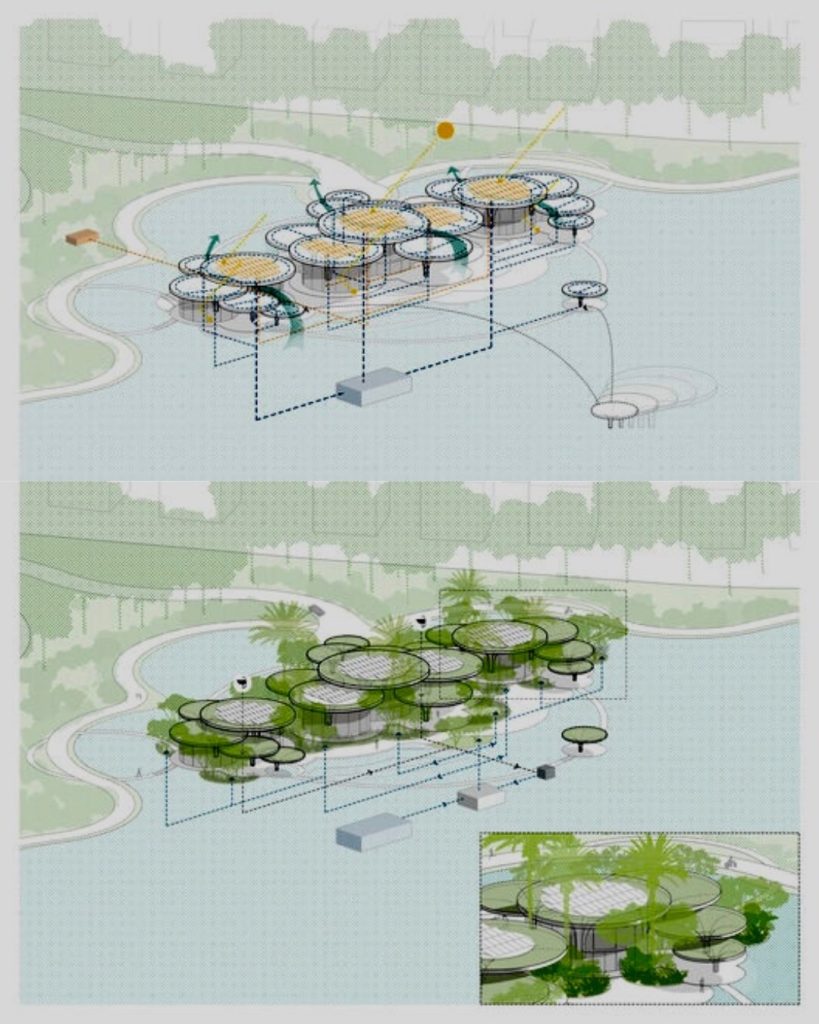

At first glance, the clubhouse appears less like a singular building and more like a carefully composed village scattered across the terrain. This dispersed layout is not merely an aesthetic choice but a strategic environmental response. By breaking the mass into smaller volumes of varying heights, the design reduces heat absorption, improves cross ventilation, and ensures that views of the natural surroundings remain uninterrupted. The result is a spatial experience that feels simultaneously expansive and intimate, open yet protective, mirroring the delicate duality inherent in tropical environments.

Also Read: Top Mexican Architects Preserving Culture Through Design

Movement through the property unfolds along gently curving pathways that resist rigid geometry in favour of organic flow. Water features accompany these routes with a quiet constancy, reflecting light, cooling the microclimate, and lending the campus an almost contemplative rhythm. There is an intentional choreography at play here: as one progresses from the animated lake facing zones into quieter recesses embedded deeper within the greenery, the architecture gradually shifts in mood. Social spaces hum with activity and collective energy, while secluded corners invite pause, introspection, and a renewed awareness of nature’s subtle textures.

Yet perhaps the most compelling gesture is found above. The layered green roofs are not decorative embellishments but performative ecological systems. Draped in vegetation, they act as natural insulators, significantly reducing indoor temperatures in Vietnam’s humid climate and lessening reliance on mechanical cooling. During heavy rains, these planted surfaces absorb and slow water runoff, mitigating the risk of flooding while replenishing the soil. Over time, they foster microhabitats that encourage birds, insects, and native plant species to reclaim territory often surrendered to development.

This integration of architecture and ecology transforms the clubhouse into a living organism rather than an inert structure. The building breathes, cools, and adapts in concert with its environment, embodying a model of low impact design that feels both pragmatic and visionary. Importantly, sustainability here is not treated as technological spectacle. There are no overt declarations, no performative displays of environmental virtue. Instead, the intelligence of the project reveals itself quietly through comfort, shade, airflow, and the persistent presence of green.

Equally notable is the project’s sensitivity to human experience. Tropical architecture has long grappled with the challenge of balancing exposure with refuge, and Lotus Clubhouse negotiates this tension with remarkable finesse. Transitional spaces blur the boundary between interior and exterior, allowing occupants to remain constantly aware of shifting light, rippling water, and the gentle movement of leaves. Such permeability fosters not only thermal comfort but also psychological ease, reminding visitors of their embeddedness within a larger ecological continuum.

In many ways, Lotus Clubhouse signals a maturation in contemporary architectural thinking across Southeast Asia. It suggests that progress need not be synonymous with excess, and that restraint can be profoundly expressive. By weaving built form into the very fabric of the landscape, the project proposes a future where development enriches rather than erases natural systems. Ultimately, the clubhouse stands as a persuasive testament to a simple yet often overlooked truth: architecture achieves its highest purpose not when it dominates nature, but when it learns to belong to it.