The tourbillon is the supercar of watchmaking. Everyone recognises it. Everyone wants to talk about it. Very few people can explain why it exists, and even fewer actually need one. It spins. It mesmerises. It costs a small fortune. And it has become shorthand for “serious watch,” even though its original job description has long since expired. At its simplest, a tourbillon places the balance wheel and escapement inside a rotating cage, usually turning once per minute. It is watchmaking gymnastics. Tiny, precise, unforgiving gymnastics. And historically, it was invented to solve a very specific problem that no longer affects us in the same way.

When Gravity Was the Enemy

Back in 1801, when Abraham-Louis Breguet introduced the tourbillon, watches lived in pockets. Upright. Still. Gravity pulled in one direction all day long, introducing errors because the balance and escapement were never perfectly symmetrical. Over time, those errors stacked up.

Breguet’s solution was brilliantly logical: rotate the entire regulating organ so gravity averaged itself out. Instead of pulling in one direction, it pulled in all of them. In a pocket watch, worn vertically for most of its life, this worked. Properly executed, a tourbillon genuinely improved accuracy. Problem solved. For about a century.

The Wristwatch Changed Everything

Once watches moved to the wrist, the rules collapsed. A wristwatch is never still. It is vertical, horizontal, upside down, shaking hands, typing emails, waving at taxis and occasionally being flung onto a bedside table. Gravity attacks from everywhere, all the time. In this environment, a tourbillon loses its advantage. Modern escapements, balance springs, free-sprung balances and advanced materials do a far better job of maintaining accuracy. In fact, many non-tourbillon movements are demonstrably more precise than tourbillons.

Which raises the obvious question. So Why Are Tourbillons Still a Thing? Because accuracy stopped being the point a long time ago. Today, the tourbillon exists as proof of mastery. It is a complication that serves no commercial purpose and offers no shortcuts. It is expensive to design, difficult to assemble, painful to regulate and completely unnecessary. Which is exactly why it matters. A brand that can build a good tourbillon is telling you it understands fundamentals at the deepest level. Power delivery. Friction management. Shock resistance. Thermal stability. You cannot fake a tourbillon. You either know what you are doing, or it will expose you publicly. Some tourbillons do still offer marginal gains in positional stability, particularly in carefully engineered systems. But mostly, they exist because mechanical watchmaking is no longer about efficiency. It is about intent.

When Tourbillons Try to Be Useful Again

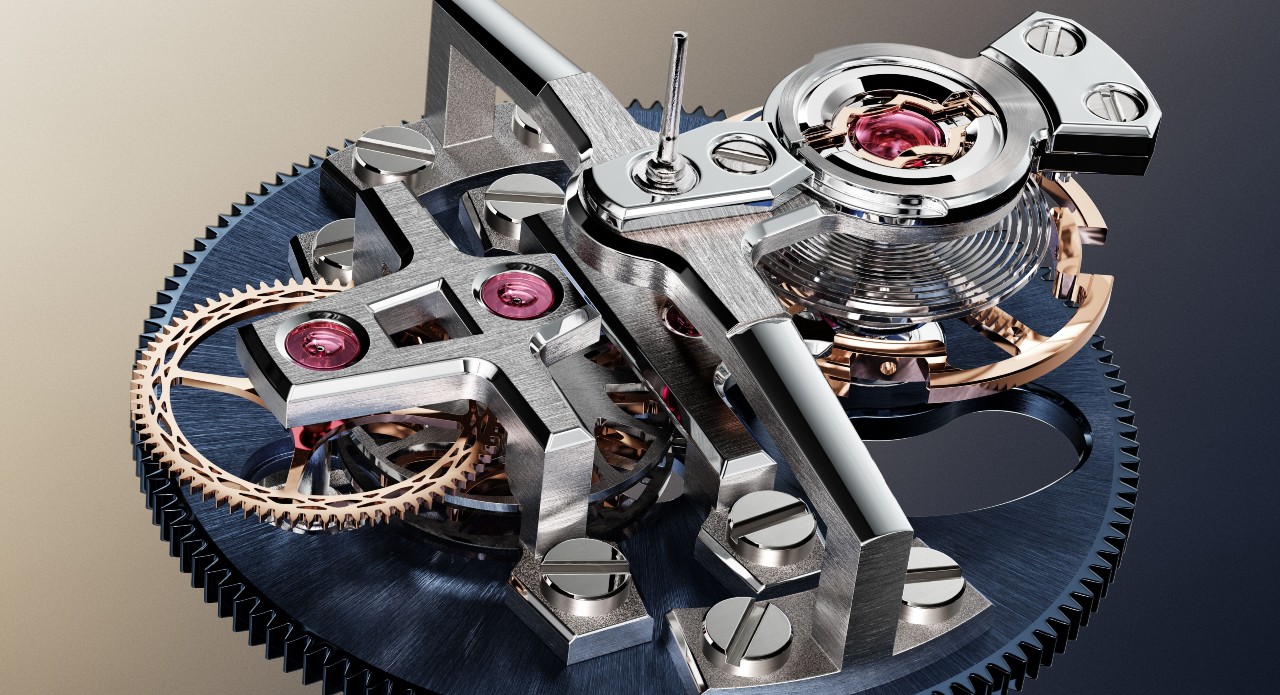

Jaeger-LeCoultre is one of the few manufactures that still treats the tourbillon as a problem to be solved rather than jewellery to be displayed. The Gyrotourbillon is the mad scientist approach. Multiple cages rotating on different axes, often paired with a spherical balance spring, all designed to average out gravitational errors across as many positions as possible. It is visually outrageous and mechanically heroic. Any accuracy benefit exists, but it comes at the cost of extreme complexity and delicate regulation.

The Duomètre Héliotourbillon, however, is the grown-up solution. Using Jaeger-LeCoultre’s twin-wing architecture, it separates the power supply for timekeeping from that of the complications. The tourbillon receives constant, stable energy, free from torque fluctuations. This is not just a spinning showpiece; it is a tourbillon given the best possible conditions to perform properly.

Tourbillons survive because watchmaking is no longer about telling time better. That battle was won decades ago by quartz. Mechanical watchmaking now exists to tell stories about human stubbornness, excess and obsession. The tourbillon is unnecessary, inefficient and utterly irrational. And that is precisely why it remains the ultimate complication. It proves that even when the problem disappears, some watchmakers will still build the solution—simply because they can.