In watchmaking, where seconds are usually encouraged to flow gracefully and minutes glide without interruption, the jumping hour does something refreshingly rude — it stops, waits, and then snaps into place. No warning. No smooth transition. Just an instant, unapologetic leap from one hour to the next. It’s the horological equivalent of punctuation: abrupt, deliberate, and impossible to ignore. If traditional watchmaking is calligraphy, the jumping hour is bold typography.

This is a complication that refuses to behave like a conventional timepiece. Instead of relying on sweeping hands or incremental progress, it presents time as a series of decisive moments. One hour ends. Another begins. Cleanly. Mechanically. Dramatically. In a world obsessed with fluidity, the jumping hour celebrates certainty — and that alone makes it quietly rebellious.

How The Hour Actually Jumps

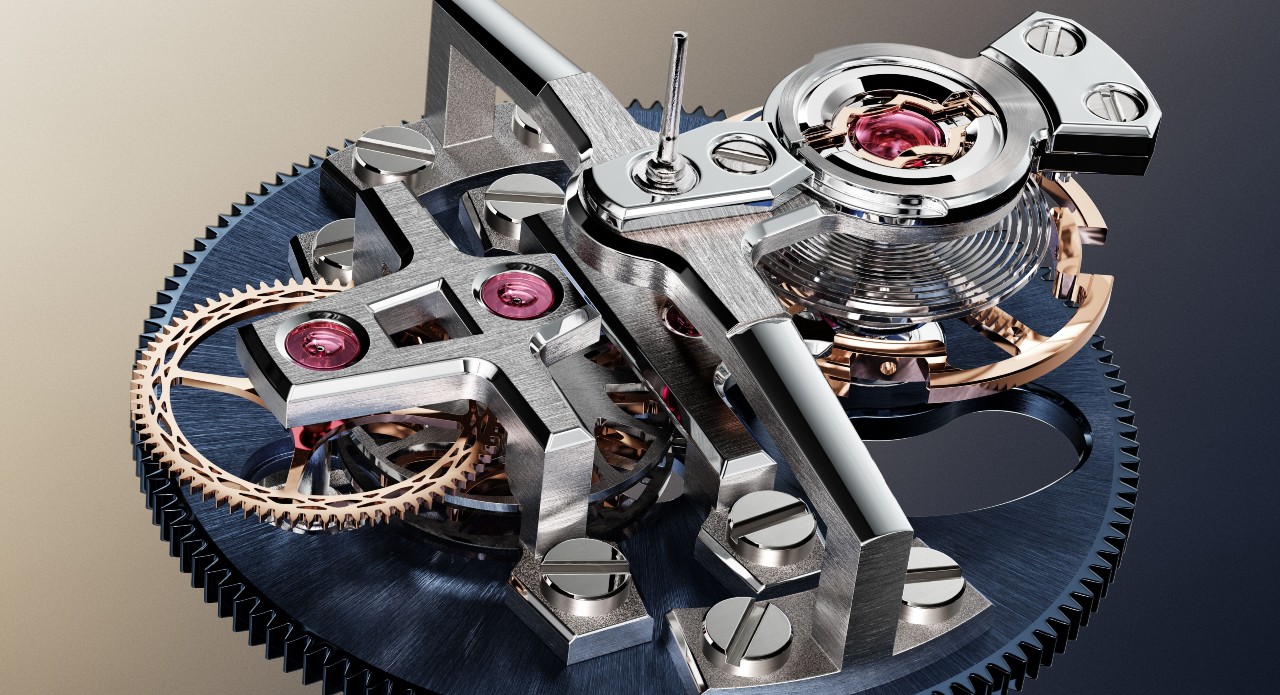

The jump may look sudden, almost effortless, but behind that split-second drama lies a carefully choreographed mechanical build-up. A jumping hour doesn’t move impulsively — it waits, storing energy with monk-like patience before releasing it with absolute precision.

Inside the movement, the minute wheel is constantly in motion, turning once every hour as the minutes progress. Connected to it is a snail cam or star wheel linked to the hour disc. As the minutes advance, a spring-loaded lever is gradually tensioned, quietly accumulating energy over the course of 60 minutes. Nothing appears to happen on the dial — the hour numeral remains frozen, teasing restraint. Then comes the moment. When the minute hand reaches the 60-minute mark, the cam reaches its release point. The tensioned spring is freed, snapping the hour disc forward exactly one increment. The old hour disappears, the new one locks cleanly into place, and the system immediately begins storing energy all over again for the next jump.

The brilliance lies in the control. The jump must be instantaneous but not violent, precise but not hesitant. Too weak, and the disc stalls mid-change. Too strong, and the mechanism suffers premature wear. Achieving that balance is one of the quiet triumphs of advanced watchmaking. In essence, the jumping hour doesn’t move like traditional time — it accumulates intention, then acts. One clean leap. One decisive moment. A mechanical reminder that time, when engineered beautifully, doesn’t need to flow to feel alive.

A 19th-Century Idea

The concept of the jumping hour dates back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries, long before digital displays became commonplace. One of the earliest known examples was commissioned in 1795 by none other than Marie Antoinette, reportedly designed to allow her to read the time discreetly during evening engagements.

By the late 1800s, jumping hour pocket watches gained popularity, particularly in Europe. They were prized not just for novelty, but for legibility — time could be read instantly, without interpretation. This was mechanical digital timekeeping before electricity ever entered the conversation.

A Complication That Refused To Disappear

Despite falling out of favour during the quartz revolution, the jumping hour never truly vanished. Instead, it found a second life in the hands of independent and avant-garde watchmakers who valued mechanical storytelling over mass appeal.

Brands like Audemars Piguet, A. Lange & Söhne, Cartier, F.P. Journe, and Urwerk reinterpreted the jumping hour in wildly different ways — from Art Deco elegance to futuristic satellite displays. Each version reinforced the same idea: this was not a gimmick. It was philosophy made mechanical.