Most architects worry about walls, roofs, and whether the budget has just exploded. Louis Kahn, however, looked at a building site and thought, “Yes, but where will the sun enter, and how will it behave when it gets there?” While the rest of modernism was busy churning out glass boxes that looked like overgrown aquariums, Kahn was orchestrating sunlight like a symphony conductor—letting it crash, pause, soften, and occasionally disappear altogether. His buildings don’t just sit in light; they wrestle with it, sculpt it, and occasionally trap it like a precious resource. Walk into a Louis Kahn building and you don’t merely see architecture—you feel time slow down, shadows lengthen, and light become something solid, deliberate, and profoundly moving.

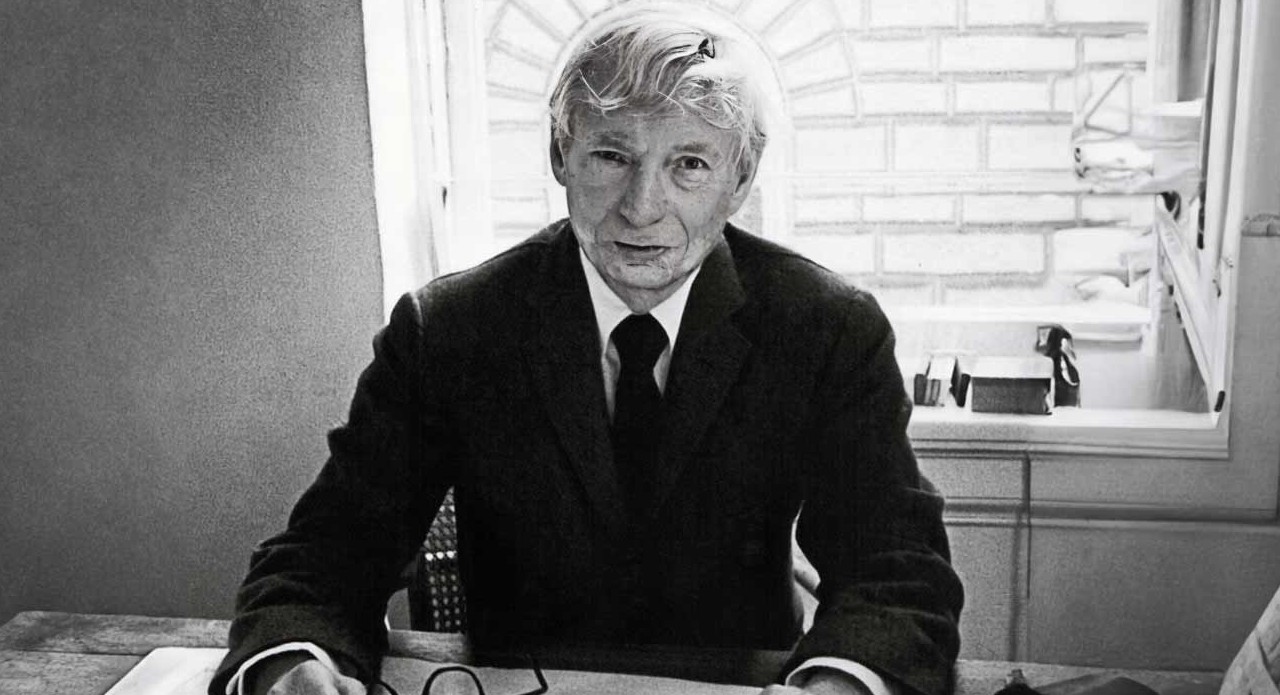

Born in 1901 in what is now Estonia and later emigrating to the United States, Louis Kahn emerged as a radical voice against the sleek, anonymous modernism of the mid-20th century. At a time when architecture was becoming lighter, faster, and more industrial, Kahn turned in the opposite direction—toward monumentality, geometry, and timelessness. He believed buildings should feel eternal, as if they had always existed. Light, for Kahn, was the key to achieving this sense of permanence.

Weight, Mass, and Shadow

At a time when modernism celebrated transparency and endless glass, Kahn went in the opposite direction. He embraced heavy materials like concrete and brick, using their thickness to carve deep shadows and frame light with almost religious intensity. Light in Kahn’s buildings does not flood in—it arrives deliberately, filtered through geometric openings and massive structural elements. This approach gave his architecture a timeless quality, closer to ancient ruins and monuments than to the sleek corporate towers of his contemporaries.

Iconic Buildings

Perhaps the most iconic expression of Kahn’s philosophy is the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. The complex is famously organised around a narrow channel of water that leads the eye—and the light—towards the Pacific Ocean. The laboratories are restrained and monumental, allowing sunlight to animate the concrete surfaces throughout the day. Here, light becomes both orientation and emotion, transforming a research facility into a place of contemplation. The building feels less designed than discovered, as if it always existed, waiting for the sun to reveal it.

At the Kimbell Art Museum, cycloid vaults and hidden skylights create galleries washed in soft, even light—proof that natural illumination can outperform artificial systems when handled with precision.

Materiality And Light Worked Together

Kahn’s choice of materials—concrete, brick, stone—was inseparable from his approach to light. These surfaces absorb, reflect, and hold illumination in ways glass never could. His buildings feel quiet because light is never harsh or accidental. Shadows are deep, deliberate, and calming. This interplay creates what many describe as architectural silence—a sense that the building is speaking softly, asking visitors to slow down and pay attention.

What makes Kahn’s work so powerful is not just light alone, but how it interacts with proportion and silence. His buildings often feel quiet, even when massive. Geometry is simple but exacting—circles, squares, and triangles arranged with almost mathematical purity. Light animates these forms slowly, changing the atmosphere without ever overwhelming it. In Kahn’s world, architecture does not rush; it asks occupants to pause, observe, and feel the passing of time.