Few architects have bent the world’s imagination quite like Zaha Hadid. The Iraqi-British architect, born in Baghdad in 1950, was a rebel visionary whose designs looked less like buildings and more like fluid dreams poured into concrete, glass, and steel. Her creations were never static; they pulsed, curved, and flowed — as if they were alive. Zaha Hadid didn’t just design structures. She sculpted sensations.

Nicknamed the Queen of the Curve, she reimagined what architecture could be in the twenty-first century. Her work shattered the rigidity of modernism, replacing straight lines with organic fluidity. To her, a building was not a box to inhabit but a landscape to explore — an extension of movement and emotion. When others saw boundaries, she saw potential.

If Zaha Hadid Designed a Desert Mansion in 2030

If Zaha Hadid were to design a desert mansion in 2030, it would not sit on the landscape — it would grow out of it. Imagine a vast expanse of sunburnt sand and pale stone, sculpted by wind and light. Rising from that terrain, her mansion would ripple like a mirage: a seamless fusion of organic curves and digital precision. The architecture would feel as though nature itself had decided to dream in concrete.

Solar panels would be integrated into flowing rooflines that mimic dunes, harvesting energy while shading interior courtyards. Water-harvesting systems would blend invisibly into the design, cooling interiors through intelligent airflow rather than mechanical dependence. Her trademark glass façades would undulate to catch the changing desert light, turning the house into a living sundial that shifts in tone and temperature through the day.

Inside, walls would dissolve into ceilings, and rooms would emerge like caverns of calm — no partitions, only transitions. Furniture would be part of the structure, carved into the architecture like fluid extensions of thought. Every surface would speak to her language of motion and rhythm.

Hadid’s desert mansion would be more than a home; it would be a dialogue between architecture and environment — technology and topography in perfect choreography.

Who Was Zaha Hadid

Zaha Hadid began her architectural journey at the Architectural Association School in London, where she developed her radical approach to form and structure. Her early drawings were so avant-garde that many believed they could never be built. But her determination and mastery of emerging digital tools turned those dreamlike concepts into reality.

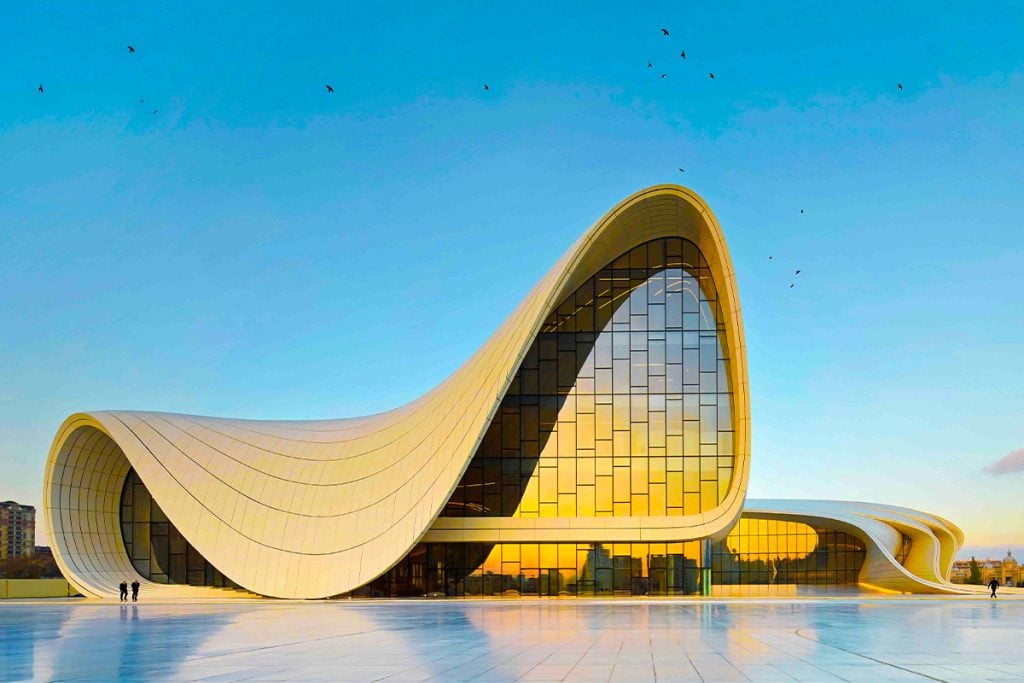

She founded Zaha Hadid Architects in 1979, and her first major breakthrough came with the Vitra Fire Station in Germany (1993) — all sharp angles and energy frozen mid-motion. From there, her career became a series of global landmarks that redefined cities: the MAXXI Museum in Rome, the Guangzhou Opera House in China, and the Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku.

Her style — often called parametricism — embraced fluid geometry, powered by advanced computational design. But behind the algorithms was an artist who wanted buildings to feel human, emotional, and alive.

Her Role in Redefining Architecture

Zaha Hadid was not just an architect; she was a cultural force. She broke through barriers in a profession long dominated by men and redefined what a woman could achieve in architecture. In 2004, she became the first woman to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize — the field’s highest honour. Her boldness inspired a generation of architects to dream beyond the possible, merging art, engineering, and philosophy into one seamless discipline.

Her architecture blurred boundaries between structure and sculpture, between environment and experience. She refused to accept that buildings had to be static; she wanted them to move with the world. Her designs were the physical embodiment of progress — futuristic, organic, and unashamedly beautiful.

The Enduring Influence

Though she passed away in 2016, Zaha Hadid’s influence has only intensified. Her firm continues to translate her futuristic ideals into reality — merging advanced computational design with a deep respect for ecology and human experience. The result is a body of work that remains defiantly ahead of its time.

If her imagined desert mansion of 2030 were to exist, it would not only embody her mastery of motion and material but also stand as a statement of how architecture can evolve with the planet rather than against it. It would remind the world that boldness and beauty are not opposites, and that the curve — her signature, her language, her spirit — still leads us towards the future she once dreamed into form.