Let us be absolutely clear about one thing right from the start. Films are not just about actors, dialogue, or explosions that cost more than a small country’s GDP. They are about where things happen. Put James Bond in a beige office block and suddenly he is no longer a suave international man of mystery. He is a middle manager waiting for a coffee refill. Architecture in cinema is the ultimate scene stealer. It tells you who is in charge, who is losing their grip, and who is about to meet a deeply unfortunate end without saying a single word. A narrow corridor makes you sweat. A cavernous hall makes you feel small. A glass house practically announces that something terrible is about to happen. In the marriage between architecture and cinema, buildings do not simply sit there looking pretty. They manipulate, intimidate, seduce, and occasionally terrify, shaping the story long before the first line of dialogue is delivered.

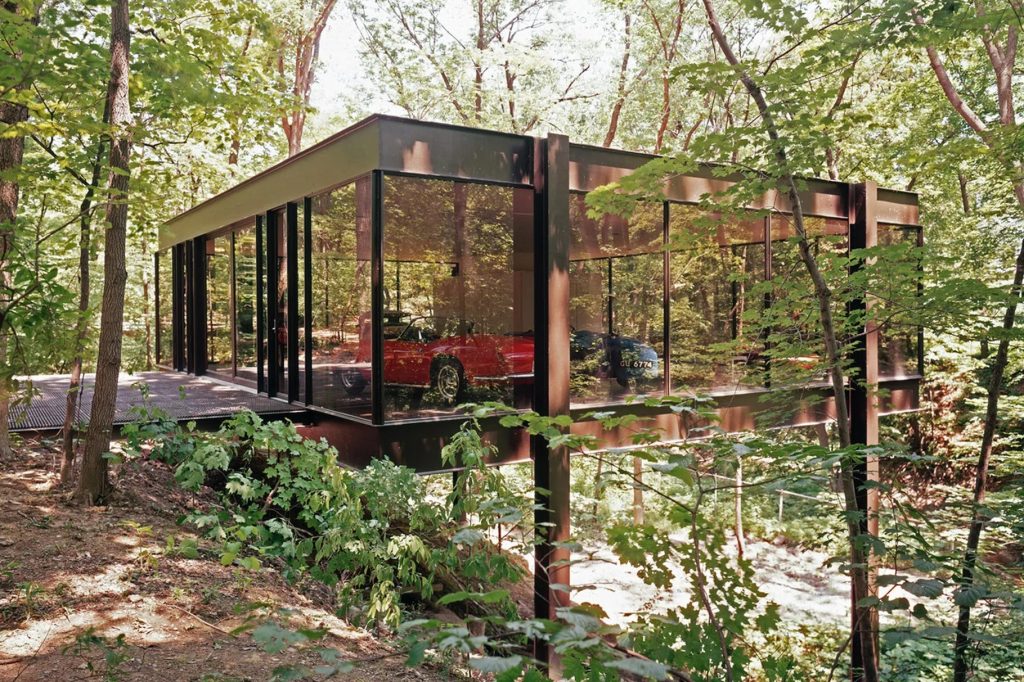

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) — Ben Rose House

The Ben Rose House is not just a backdrop for Ferris Bueller’s carefree rebellion. It is the physical embodiment of suburban freedom done properly. All glass, steel, and unapologetic modernism, the house feels more like a manifesto than a family home. It mirrors Ferris himself. Calm, confident, and completely unbothered by authority. The floating staircase, the transparency, and the way the car is displayed like a museum piece turn the space into a quiet accomplice in the story. This is architecture that refuses to panic, even when a priceless Ferrari is dangling over disaster.

Also Read: Top Chilean Architects Shaping Sustainable And Social Architecture

Ex Machina (2014) — Juvet Landscape Hotel

Juvet Landscape Hotel does not look like a place where things will end well, and that is precisely the point. Embedded into the Norwegian wilderness, the architecture feels clinical, isolated, and eerily polite. Glass walls blur the line between interior and exterior, creating a sense of constant surveillance. Nature is visible everywhere, yet utterly unreachable. The building reinforces the film’s central tension. Technology wrapped in beauty, control disguised as minimalism. The house is a cage with excellent taste, and the more time you spend inside it, the clearer it becomes that escape was never part of the design.

Blade Runner (1982) — Ennis House

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House gives Blade Runner its weight, its menace, and its brutal beauty. The concrete block structure feels ancient and futuristic at the same time, like a ruined temple from a civilisation that has not yet existed. Inside, the shadows stretch, the textures press in, and the walls seem to breathe. This is not a comfortable space. It is oppressive, monumental, and heavy with existential dread. The architecture amplifies the film’s central question about humanity by making the characters look small, fragile, and temporary within something that feels eternal.

Le Mépris (1963) — Casa Malaparte

Casa Malaparte is not merely a house perched on a cliff. It is an argument. Sharp, isolated, and defiantly geometric, it dominates the landscape rather than blending into it. In Le Mépris, the house becomes a silent witness to emotional disintegration. Its long, exposed terraces and stark interiors leave nowhere to hide, visually or psychologically. Every argument feels louder, every silence heavier. The architecture does not soften the drama. It sharpens it. Love unravels here not in shadows, but in full Mediterranean sunlight.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) — Seagram Building

The Seagram Building represents aspiration in its purest form. Clean lines, disciplined modernism, and an almost intimidating elegance define the spaces used in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. This is architecture as ambition made visible. The building’s restraint mirrors Holly Golightly’s carefully constructed persona. Polished on the surface, fragile underneath. The corporate modernism of the Seagram Building grounds the film in a New York that is sophisticated, aloof, and ruthlessly stylish. It is the perfect architectural counterpoint to a character chasing glamour while quietly fearing stillness.